BY VI KHI NAO

in conversation with CHRISTINE SHAN SHAN HOU

VI KHI NAO: How would you describe your poetry and your art (collage)? Do they seem similar to you? How close do you feel to Dadaism? Is there a particular literary movement or artistic movement you wish had been invented?

CHRISTINE SHAN SHAN HOU: I look at both my poems and my collages like miniature worlds—each filled with their own characters, tastes, textures, and elements of strangeness and love. However, I actually feel like my poetry and collage are quite different from one another; my poetry—specifically the process of writing poetry—feels heavier, darker, whereas my collages feel lighter and more directly pleasurable. Writing poetry is hard. Collaging is fun. I don’t feel particularly close to Dadaism. I remember studying them in college and being very excited at first, but now I look at them and think: Look at all those old white men! Now that we’ve seen the first image of the black hole, I wonder: What would movement look like in a black hole?

VKN: Your collection, Community Garden For Lonely Girls, shows that you have a natural linguistic impulse to produce words/thoughts that mirror each other—as if you were trying to use the rhetoric of repetition to create content by allowing it to erase itself through doubling. For example, lines such as “my ancestors’ ghosts have ghosts” (p.3), “my split ends have split ends” (p. 4), “If I lay here, how long will I lay here?” (p. 18), “Act without acting out” (p.54), etc. Do you prefer sentences/lines that never look at each other or always look at each other?

When you write these lines, I think that your poetry uses symmetry as a way to acknowledge the lexical self they haven’t been able to access; when a particular word repeats itself in the same context, it brings something out. What do you hope to bring out? In each other, meaning poetry and yourself.

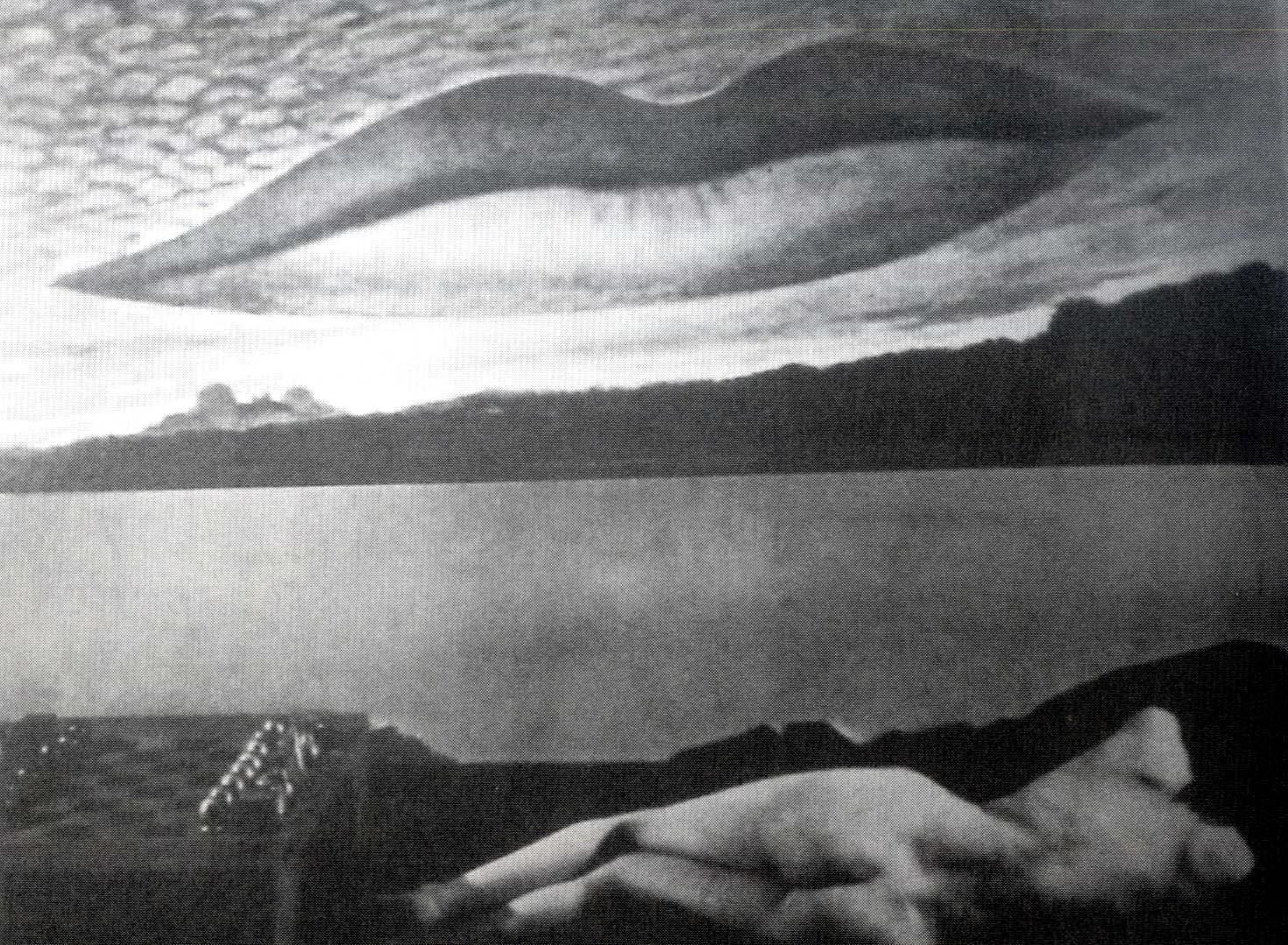

CSSH: I love this question, this image, of two sentences/lines looking at each other. It brings to mind an artwork by the Korean artist, Koo Jeong A. She made this one piece called Ousss Sister (2010) where two projections of the full moon are facing each other within a very narrow space. It is so bewildering, this concept of a self without eyes looking at one’s self. Is this still considered “looking” if one can’t see? Does one have to have eyes in order to have a face? I prefer sentences that look at each other, even though my sentences don’t always have eyes. Meaning arises from the act of looking. Repetition ensures its existence. Where there is existence, there is possibility bubbling beneath the surface. When I repeat words within sentence structures I am suggesting a possibility. A possibility for what? I don’t know.

When people read my poetry their hair grows a little longer.

VKN: That is a mesmerizing image from Koo Jeong A. It reminds me of a pair of lungs. If your collages and your poems were to arm-wrestle each other and the yoga instructor/practitioner in you was forced to be the ultimate referee, who would win that tournament? And, ideally, which two aesthetic competitors would you like to see compete with each other in a match? Would you prefer to be the cheerleader or the umpire? If the winner between the two mentioned competitors (collages & poems) is the one who is able to break a reader/viewer’s aesthetic heart the fastest, which one would it be?

CSSH: My collages would definitely win! My visual art feels lighter and not so bogged down by my past, by my thoughts, or by the heaviness of the language in the air! When I make collages, I am often listening to a podcast, or music, or have a tv show on in the background, all of which feels good for my brain, whereas when I am writing poetry, I can’t have any other distractions. I have to be very in it. One could argue that this extreme awareness of the present when writing poetry seems more mindful than the multitasking of collaging, but ultimately for me, the collage process is much more enjoyable, and the yoga instructor in me will lean towards the direction of joy. I think my collages would break the reader/viewer’s aesthetic heart the fastest.

I would love to see film go head-to-head with any form of live art.

VKN: Why do you want your readers’ hair to grow a little longer? I would hope it would grow shorter, to defy the law of gravity or the law of expansion.

CSSH: Honestly, I don’t know why! It was just an image that floated into my head. I think it’s because I equate growing hair to growing older, which also means growing calmer.

VKN: You are currently a poetry professor at Columbia. Do you enjoy teaching? Would you ever play a prank on your students? If so, what would be one prank that would bring out your impishness? What collage of yours or poem of yours would be a great example of a prank? What poem or collage of yours (or someone else’s) would be equivalent to this prank? And, what is the best way for a student of the arts or in general to express rebellion?

CSSH: I do enjoy teaching. It is very invigorating to be in a room with young people who are as excited by poetry as me! However, to be honest, I prefer teaching yoga over teaching poetry. I’m not much of a prankster, but the poem that is closest to a prank is “Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove it” in Community Garden For Lonely Girls

That prank is very funny, but also mean. I think I’m too sensitive for pranks. I realize that makes me sound a little bit like a wet blanket, but I am ok with that. I think the best way for a student of the arts to express rebellion is to pursue the practice outside of the academic institution and at one’s own pace, whether that pace is a sprint or a crawl.

VKN: I view pranks as one way or a tool an artist can use to express him or herself creatively in a comedic fashion. My brother sent me that prank at a sad point in my life, and it cheered me up and made me feel closer to him. I do not view it as a gesture of meanness, as in: shampoo is just shampoo and irritation is irritation and water running down one’s face excessively once every millennium is a divine act of profound charity.

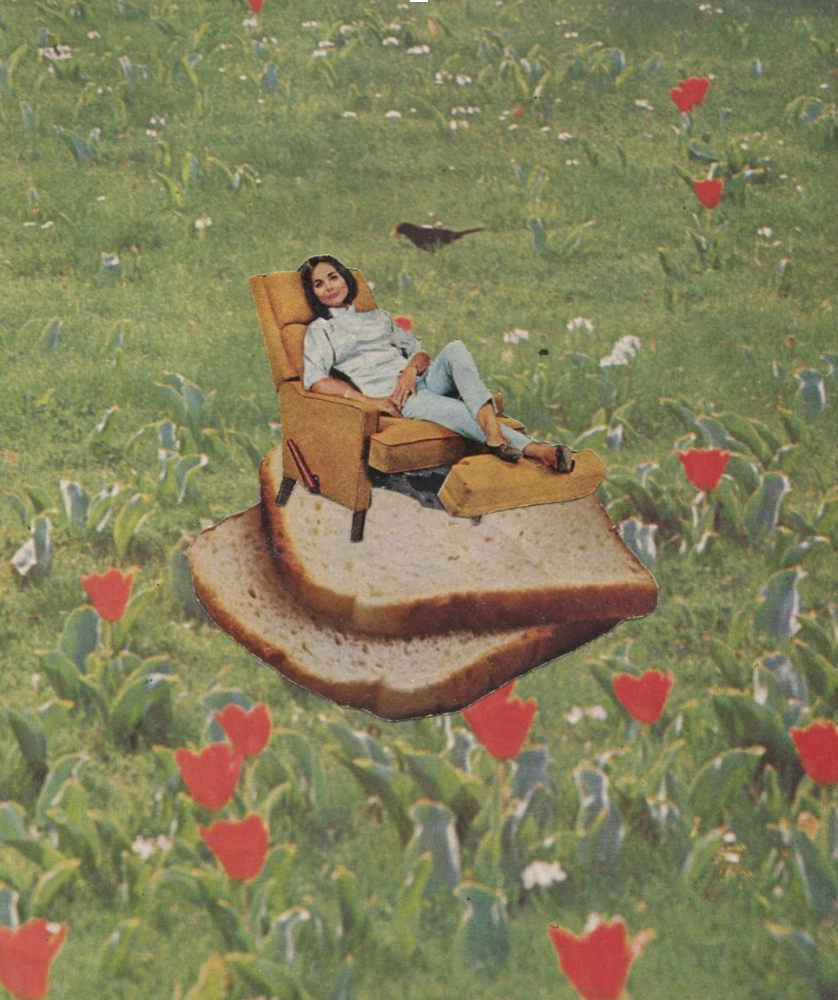

Speaking of visual or kinetic creativity, one can view your visual works on your Instagram: hypothetical arrangement. Can you talk about the piece below? Can you walk us through the process of how you created it? From seed of conception to final product?

How often do you make your collages? I know you have one daughter, but in terms of sibling rivalry (how many of you are there, btw?), has poetry ever fought with you for creative space because you devote more time to one discipline or art form rather than another? You must understand scissors and surgical knives very well. Do you ever feel like you are a surgeon? Have you ever created a collage where you feel like you are performing a heart surgery and the life of this art piece heavily depends on how well you incise? Have you ever cut through the artery of an image and felt lost or lonely or regretful or sorrowful or overjoyed?

CSSH: This collage is called “Self-actualization (in recline).” When I make collages I go through old magazines and start cutting out images that speak to me. I have several categories for images and three of them are: food, women, and seascape/landscape. I don’t remember how I arrived at this final image, but I remember liking the way the red flowers contrasted with the dreary, soft slices of bread and then the ease of the woman’s posture. I like her shimmering periwinkle outfit and her pet bird in the background.

I try to make at least one collage a week, but that doesn’t always happen. I tend to make many collages in a short period of time, or even in one sitting, and then occasionally mess with them for a few minutes every few days, until I feel satisfied with them.

I am one out of four siblings. However I do not see any “sibling rivalry” between poetry and my yoga and/or collage practice. I think they all work in harmony with one another and give each other the time and space to breathe.

Yes! I definitely feel like a surgeon when I am making collages. I use an x-acto knife so I can really get into the details. And there are so many pieces I’ve considered “ruined” or “dead” because I was too impatient with the cutting of a very precise detail. But then I immediately let it go. I try not to get too precious about paper arteries.

VKN: Will you break down the poem “A History of Detainment” (p. 72) or (“Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove it,” or why this poem may feel pranky to you) from your collection, Community Garden For Lonely Girls, for us, Christine? Can you talk about the process of writing that poem? Do you recall writing it? What was it like? Where were you emotionally? Intellectually? Were you preparing a meal? On a train? Or what piece of writing/art inspired it? Did it take you long? And, could you talk to us about this line: “While navigating the meadow of hypotheticals, I tripped and broke my arm” (p.72). If you broke your arm, what one line from a canonized poet would you want to scribble on your cast?

CSSH: “A History of Detainment” is so long and heavy and my brain is so tired after a full day of running around with my kid. But I can say a little bit about “Masculinity and the Imperative to Prove It”: When I was a child, my grandparents owned a Chinese restaurant called Oriental Court inside of a New Jersey shopping mall. Every Saturday night my entire paternal family—grandparents, all of their children and all of their children's children—would eat dinner after the mall's closing hours. After the meal, me, my siblings, and my cousins would run around like crazed little people in the empty mall and play all sorts of games including: "Red Light Green Light," "Red Rover," "What Time is it Mr. Fox?" and "Mother May I."

However, the golden rule was that we had to wait at least thirty minutes after eating before engaging in any physical activity, or you would get sick. When I was a young girl, I was often ashamed of my body. I used to wish that I were white so that I could fit in with the popular crowd; I would make myself throw up because I thought I was fat; and because I was sick a lot as a child, I would view my medical issues as a reflection of moral shortcomings. In other words, I was a very sad child. But at the end of the poem, the sad child is actually a fish. And we all know that a salad can be both a curse and a blessing.

VKN: That’s a very beautiful story, Christine. I understand your tiredness. Perhaps this last question then: What do you think is the best way for one poet to feel at home in a poetry collection by another poet?

CSSH: Poetry collections are like homes unto themselves. I think the best way for a poet to feel at home in someone else’s poetry collection is by taking their time while reading it and listening closely, attentively, to what it is trying to say.

Christine Shan Shan Hou is a poet and visual artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Publications include Community Garden for Lonely Girls (Gramma Poetry 2017),“I'm Sunlight” (The Song Cave 2016), and C O N C R E T E S O U N D (2011) a collaborative artists’ book with Audra Wolowiec. She currently teaches yoga in Brooklyn and poetry at Columbia University. christinehou.com

VI KHI NAO is the author of Sheep Machine (Black Sun Lit, 2018) and Umbilical Hospital (Press 1913, 2017), and of the short stories collection, A Brief Alphabet of Torture, which won FC2’s Ronald Sukenick Innovative Fiction Prize in 2016, the novel, Fish in Exile (Coffee House Press, 2016), and the poetry collection, The Old Philosopher, which won the Nightboat Books Prize for Poetry in 2014. Her work includes poetry, fiction, film and cross-genre collaboration. Her stories, poems, and drawings have appeared in NOON, Ploughshares, Black Warrior Review and BOMB, among others. She holds an MFA in fiction from Brown University.