BY LISA MARIE BASILE

I am fortunate to receive tons of wonderful books on a wide range of topics, but some of my favorites include those by talented witches and magical beings whose books approach magic in accessible, inclusive, radical, and fresh ways.

I am always on the lookout for books which a) present an updated look at magic and witchcraft to a modern audience, b) frame witchcraft in a way that is inclusive and holistic — meaning it addresses systemic issues in society, and c) blend and blur genres — books of narrative non-fiction alongside research, poetry entwined with spellcraft, or divination techniques alongside storytelling.

Personally, I love books that can be read through an open-ended and intuitive lense, and approaches that permit those of us from even an eclectic or secular background to take part. I think all of the below books make space for the witch, the feminist, the curious, and anyone in between. So, for witches and non-witches alike, these are the books I’ve been reading as of late:

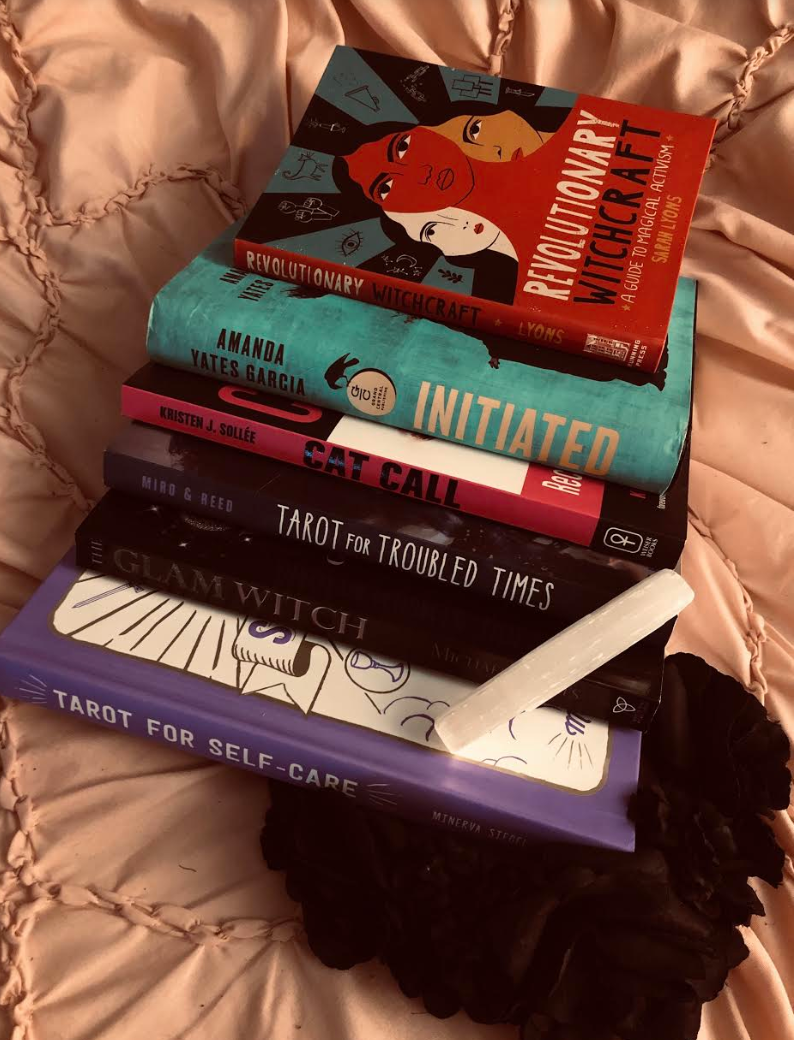

THE GLAM WITCH

I LOVE this book. Michael Herkes’ voice is a dream. His passion is palpable, lifting out of the pages and into your hands and heart. It looks at how the goddess/archetype Lilith has for so long been worshipped and feared, and walks readers through how they can create a relationship with Lilith, as well. In fact, it’s called The GLAM Witch because Herkes explores the Great Lilithian Arcane Mysteries (GLAM). Through luminous text, you’ll find astrology, ritual, and a magic that is steeped in power.

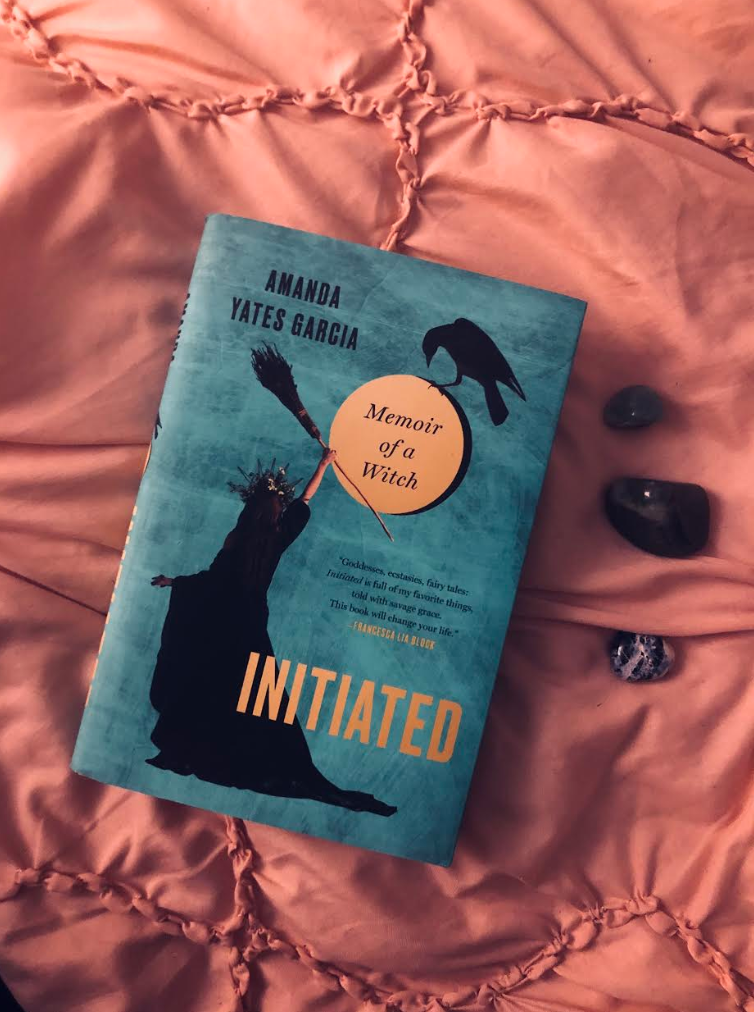

INITIATED: Memoir of a witch

Amanda Yates Garcia — known as the Oracle of LA — writes a potent story of becoming and reclamation in Initiated, which shows how she became a High Priestess, and how she tapped into her inner power. With her shedding light on feminism, culture, earth, sex work and poverty, the underlying message here is one that matters most in today’s world.

Also read: 7 magical & inclusive new books witches must read

TAROT FOR TROUBLED TIMES: CONFRONT YOUR SHADOW, HEAL YOURSELF, TRANSFORM THE WORLD

In Theresa Reed and Shaheen Miro’s Tarot for Troubled Times, we see a radical and transformational text that uses shadow work (a throughline of the book), archetypes, reflections, and prompts to reframe the power of tarot. I can’t get enough of this one. And I’ve had the pleasure of knowing Theresa (The Tarot Lady) for quite some time. Her generosity, support, wisdom, and love for magic is a continual inspiration to me.

HONORING YOUR ANCESTORS: A Guide to Ancestral Veneration

As someone who has always been interested in ancestor veneration in a specific sense — more in my writing practices than anything else — I have not read a book on the topic that has so deeply and beautifully spoken to my needs. Mallorie Vaudoise’s book does not go into the topic lightly, addressing plenty of the big issues — like not knowing who your ancestors are, for one. The book explores everything from making ancestral altars and spell-work to mediumship. It’s splendid and healing.

Read also: 4 witchy podcasts you need in your life

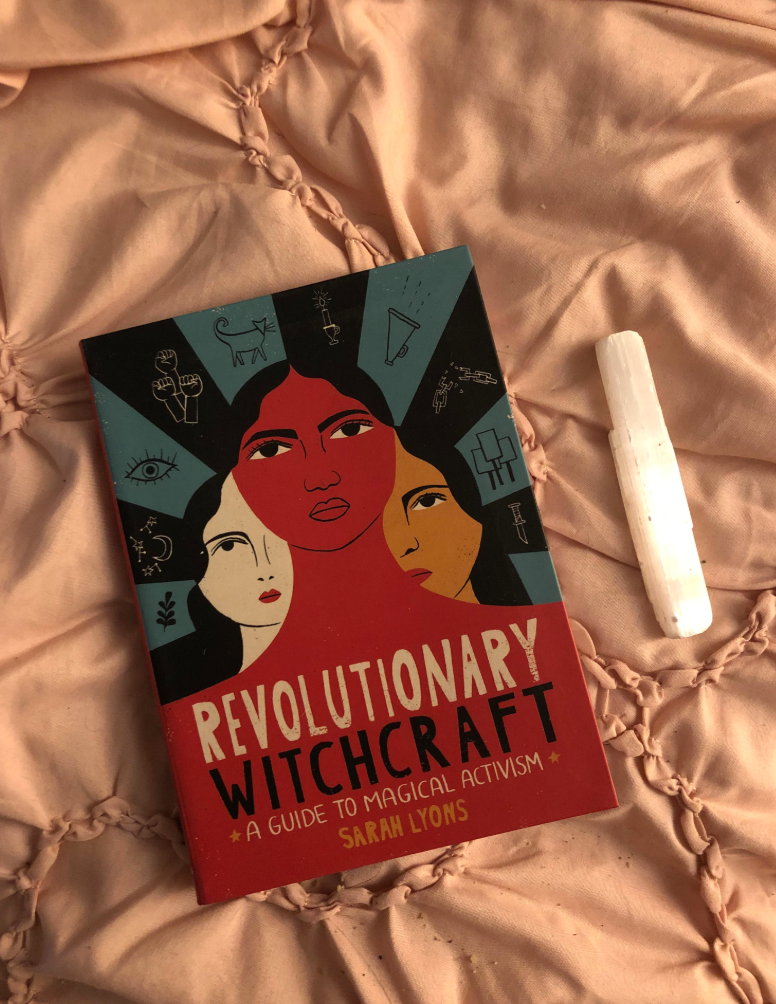

REVOLUTIONARY WITCHCRAFT: A GUIDE TO MAGICAL ACTIVISM

In Sara Lyon’s work, we find a potent and necessary look at how we can make magic in a world that is too often broken by hatred, fear. It is a world that needs transformation, and witches have that very power. I have always thought that the witch was a political figure, whether or not one intends or feels that way. Witches have long stood for the marginalized, the forgotten, the invisible. And power, as Lyons says, is political. With topics ranging from history, magic (ancestral magic, sigil creation, and spells), ally-ship and the natural world, this book is a must-have for today’s practicing witch. I also love its inclusion of the Trans Right of Ancestor Elevation, which is a ritual for trans and GNC witches to honor their ancestors of spirit killed by murder.

CAT CALL: RECLAIMING THE FERAL FEMININE

I have long been a fan of Kristen Sollée’s work (and her person) and I am indebted to her for the knowledge and support she has given me, and the magic she has brought to my life (and all of ours!) through her words. As an intersectional feminist and a witch, her books (do yourself a favor and also read Witches, Sluts Feminists) speak power into my world. In Cat Call, she brings the histories, superstitions, stories, and mythos of the feline to life, and weaves all of that into how we understand (and can better understand) sex and femininity and taboo. Fuck yes.

TAROT FOR SELF CARE: HOW TO USE TAROT TO MANIFEST YOUR BEST SELF

I love Minerva Siegel’s book for its simplicity and care. It walks readers through the tarot with care and ease, feels inclusive and avoids culturally appropriative terms, and addresses some of the big obstacles to our self-care practices. It frames the book so that it covers mental, physical and spiritual self-care, while walking you through each card and its magic.

OTHER BOOKS I’VE BEEN READING OR LOOKING FORWARD TO READING:

Pam Grossman’s Waking The Witch, Theresa Reed’s Astrology for Real Life, Astrea Taylor’s Intuitive Witchcraft, Apocalyptic Witchcraft by Peter Grey, Gabriela Herstik’s Bewitching The Elements, Juliet Diaz’ Witchery, Working Conjure by Hoodoo Sen Moise, The Door to Witchcraft by Tonya A Brown, The Astrology of Sex & Love by Anabel Gat, Weaving The Liminal by Laura Tempest Zakroff,

IAlso recommended: Catland Book’s Monthly Reader’s Coven (which I subscribe to, and which delivers gorgeous books to my door, monthly).

Lisa Marie Basile is the founding creative director of Luna Luna Magazine--a popular magazine focused on literature, magical living, and identity. She is the author of "Light Magic for Dark Times," a modern collection of inspired rituals and daily practices, as well as "The Magical Writing Grimoire: Use the Word as Your Wand for Magic, Manifestation & Ritual." She can be found writing about trauma recovery, writing as a healing tool, chronic illness, everyday magic, and poetry. She's written for The New York Times, Refinery 29, Self, Chakrubs, Marie Claire, Narratively, Catapult, Sabat Magazine, Healthline, Bust, Hello Giggles, Grimoire Magazine, and more. Lisa Marie has taught writing and ritual workshops at HausWitch in Salem, MA, Manhattanville College, and Pace University. She earned a Masters's degree in Writing from The New School and studied literature and psychology as an undergraduate at Pace University.